Heritage

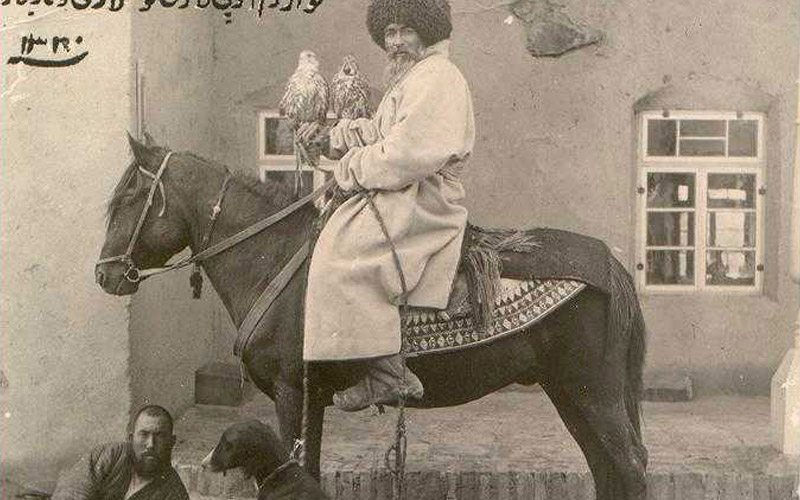

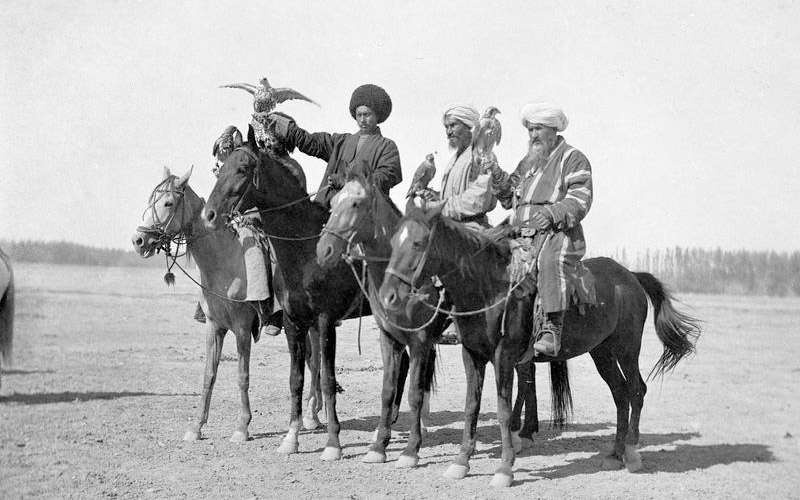

From the earliest times, hunting with birds of prey has been part of the cultural traditions of Uzbek people. Falconry in Uzbekistan has a lot of history and many traditions attached to it, which are shown in many historical sources.

The talented commander, Amir Temur, encouraged his warriors to hunt with birds of prey. He would even participate in the hunt on his rare days of recreation, as he had his own exceptionally trained golden eagle. The emirs’ favourite leisure and passion while falcon hunting is beautifully depicted in the artistic miniature poems of Alisher Navoiy: “The Turmoil of the Righteous”, “Farhad and Shirin”, “Leila and Majnun”, “The Seven Planets”, “Iskandar’s Wall” and “The Language of Birds”.

One of the documents, which is preserved in the Bodleian library at The University of Oxford, illustrates the scene “Expecting Guests”, in which the courtiers stand with a falcon, dressed in a special gilded attire and fairest leather harness. The document also illustrates a golden diamond helm which is adorned with owl feathers, a silver bell, and a glove specifically crafted for those who interact with hunting birds.

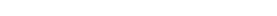

Separate from them, in between the others is a miniature that is currently housed in the Freer art gallery in Washington. According to the famous scientist and orientalist, the late G. A. Pugachenkova, in this miniature we see an image of Mirzo Ulugbek. The great astronomer is shown to be engaging in falconry. In the miniature, made in 1441-1442, Mirzo Ulugbek is depicted at the center of the composition, sitting in the luxurious Royal tent. Above it is inscribed: "Let the reign of the great Sultan, Ulugbek Guragan be everlasting". Mirzo Ulugbek was a lover of falconry. Not only special equipment, but also hunting drums were made for use whilst the noblemen were hunting. With their help, birds were frightened in to the open and falcons, hawks and other hunting birds were sent after them.

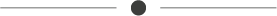

Ali Kushchi, a scientist, astronomer and mathematician, named Ptolemy of the East, played a major role in the scientific life of Samarkand, and even in the personal life of Ulugbek. The nickname given to him in his youth was ‘qushji’ - the falconer: as a favourite of Ulugbek, he was granted the honour of hunting with the Royal Falcon and was later put in charge of the Khan's hunting. Ulugbek was Kushchi’s patron; he called him his son and fully trusted him.

Ali-Kushchi

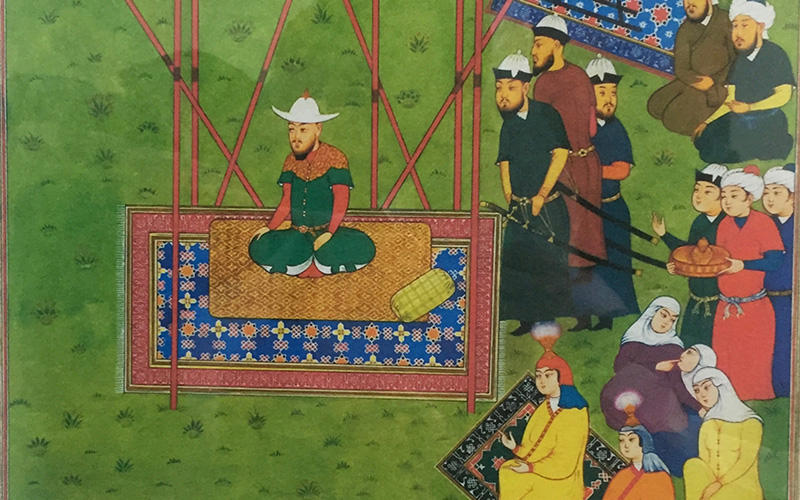

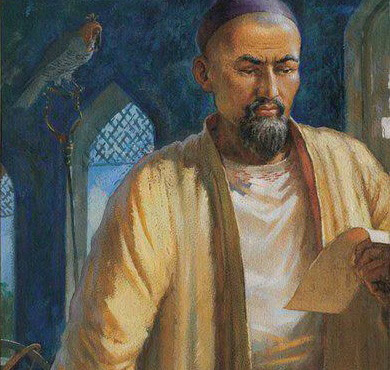

Nikolay Nikolayevich Karazin | Falconry

Falconry is featured repeatedly in Babur’s memoirs “Baburnama” (The Notes of Babur). He writes the following:

- Regarding the Sultan Ahmed Mirzo: «He was a lover of falconry; he set loose many birds, and he did this well. After Mirzo Ulugbek, there was not a second falcon-prince»

- Regarding Dervish Muhammad Tarkhan: «...He knew perfectly the habits of birds of prey, and set loose falcons with great ease.»

- Regarding Baku Tarkhan: «...he had a great propensity for falconry; it is said that he owned 700 hunting birds.»

- Regarding Hadji Mulla Sadra: «He knew both how to raise hunting birds and how to make it rain.»

- Regarding Muhammed Burundke: «…the man was very knowledgeable and a great leader. He loved the falcons to the extent that if a falcon had died or disappeared, Muhammed Burundke Barlas would mention the names of his sons and say, "That so-and-so died, or why couldn’t so-and-so have broken his neck before a falcon died or was lost».

In almost every one of Babur’s memoirs, in some way or another, there is a reference to falconry and to how the expressed person relates to hunting birds. This suggests that falconry was an integral part of the daily lives of royalty during the time of Babur.

In addition, Babur writes about himself:

- «On that day I lost a fine falcon, whom Sheikh Mir-I shikar had raised. He would catch cranes and storks with ease and even escaped two-three times. This falcon would catch birds so skillfully, that he would even turn an indifferent man to falconry, such as myself, into a falconer.»;

- «Indeed, few places will be found where it is so pleasant that one can walk in spring, set loose falcons and catch birds… »;

- «While we were at the winter camp, I would go out on the hunt two to three times a day… we would hunt for bugu-marals or… we would set up a perimeter and let loose the falcons on pheasants. The pheasants there, were infinite in number.»

The final quote indicates that, at times, falconry served as a basis for feeding men at war during long-lasting military campaigns and winter encampments.

Furthermore, in ancient times, birds of prey were not only hunters and companions of noblemen, but were also used in the branch of state diplomacy, as a precious gift and a sign of favour.

And so, Babur writes:

- «On Friday Muhammed Ali Haidar rikabdar caught a white falcon and presented it to me»;

- «We sent a falcon to Sultan Ibrahim and requested land for ourselves, which had belonged to the Turkoman from times of old.».

Another interesting fact about the traditions of falconry in Uzbekistan is contained in the travel notes of French geographer, Gabriel Bonvalot, at the beginning of the 19th century:

«Rolling in greenery, like many other cities in Central Asia, Sherabad consisted of a suburb, a market and a fortress, where the ruler of the city (the Bek) resided. The travelers’ accommodation, provided by Bek, appointed to travellers, was not distinguished with large comforts, but it was chilly and quiet in the room, and one could settle down to rest with pleasure. Bek’s son organised an unusual pastime in honour of Bonvalo and Alfred Capus - falconry. It took place on the suburbs of the city, in ponds populated with waterfowl. Early in the morning, the travellers set off on horseback, accompanied by a falconer. Strapped to his horse’s saddle was a small hunting drum, and on his arm, donned with a glove, sat a falcon, whose head was covered by a small leather cowl. First, the falconer frightened the birds away with the sounds of the drum, then he brusquely tore off the falcon’s cowl and launched it into the air. Due to the abundance of birds, the falcon would effortlessly find and kill its victim with a strike of its powerful beak. The master would return it to its place, and the entire process would then start over. This was a picturesque spectacle, which the French people had never seen».

Central Asia was rich in its traditions relating to falconry. Using goshawks, hunters caught pheasants, hares and waterfowl (ducks, teals, stitchtails and coots). Sparrow hawks were sent after hares, chipmunks and partridges. Prey of the Shaheen and Babary falcons included wild rocky pigeons, partridges, and occasionally Ulary - mountain turkey.

These are therefore the main traditions surrounding falconry in Uzbekistan, that have existed since antiquity and that we are determined to revive in a new, environmental conscious way.

1. Babur. Baburnama. Azimdzhanovoy S.A.Tashkent: Institute of Oriental Studies RUz.1993.

2) Mukminova RG Handicrafts in Samarkand in the time of Ulugbek. Collection of articles "Social Sciences in Uzbekistan», №7. 1994.

Materials used:

1) R. Mirzaev "Unknown Asia" Gabriel Bonvalot.

2) Simakov GN "Falconry and the cult of birds of prey among the peoples of Central Asia and Kazakhstan (ritualistic and practical aspects)". 1998.

You can also read:

The revived legend of the Falcon